Are you suddenly homeschooling? Maybe you’ve made the choice to do it long-term. We’re here to make sure it’s a joyful and fun experience—it doesn’t have to be daunting and overwhelming. We’ve created a four-part series of easy homeschooling tips and inspiration for anyone starting out (and for veterans too!). These tips are from Entropy Academy, a homeschooling parent’s memoir full of guidance and inspiration for anyone educating their kids outside of the institution of public education, temporarily or otherwise. In this memoir, Alison Bernhoft recounts how she discovered that she could train her messy home to do half her teaching, while much of the other half unfolded “entropy style”—in the natural process of everyday life. You can homeschool too!

Reading Aloud

One cupboard in the kitchen was devoted to puzzles, current read-alouds, and building toys. A jigsaw puzzle would often fill that difficult “arsenic hour” before dinner, while building spatial discrimination and fine motor skills. Building toys of all descriptions were a regular hazard in negotiating safe passage across the floor. As tempting as it was to confine the mess to a computer screen and purchase virtual Lego, I’m glad I didn’t. Manually manipulating real objects in three dimensions plays a vital role in brain development, and besides, it’s a lot more satisfying to show off colorful 3-D creations to an admiring audience when they can be tripped over.

This cupboard was raided at reading-aloud time, which usually happened twice a day and formed the backbone of the children’s education. I tended to gear the books to the eldest, and the younger ones were free to sit in. It was amazing to me how much they understood, even in difficult books. Rather against my better judgment, I found myself reading Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations when Sheila was only two, and I wondered if the book meant anything to her at all. Right on cue, she removed her nose from her drawing to ask why Pip’s sister was so unkind to him. Apparently she was following the action quite well. Given a steady diet of difficult books, she would undoubtedly have lost interest—but one thrown into the mix here and there seemed to whet her appetite for more.

The price of finding good books to read aloud was eternal vigilance. Notebook in hand, I scoured books such as Jim Trelease’s The Read-Aloud Handbook, listing unfamiliar authors that looked promising and hoping their output was not marred by the unevenness that seems to plague some writers.

Reading a variety of reviews helped. I tried to select a variety of books, not just fiction. I regret now not having read more biographies—for some inexplicable reason I thought they would be boring. How wrong I was! It is both fascinating and inspiring to read about the hardships and obstacles most great people have had to overcome. We tend to think that life should be easy, and strive to make it so for our children, but the truth is that most famous people have had to struggle, often against overwhelming odds, to become who they are.

I am reminded of a story about a butterfly enthusiast who witnessed a very rare butterfly struggling to emerge from its chrysalis. Only the tip of one wing remained trapped. Seeking to help, the man took a small pair of scissors and carefully snipped the chrysalis to free the wing. The butterfly spread its wings in the sun to dry. To his horror, the man saw that the part of the wing he had freed remained crumpled; it never became strong enough to fly. Apparently, struggle was necessary for the creature to be properly formed. The same seems to be true of humans. I’m not saying we should deprive our children or deliberately cause them hardships—no doubt life will provide them plenty—but by all means read to them about those who have faced difficulties and disappointments and overcome them. As Theodore Roosevelt said, “I have never in my life envied a human being who led an easy life. I have envied a great many people who led difficult lives and led them well.”

It seems I was not alone in my suspicion of biographies: when Lorna selected a volume on the life and times of Franz Josef Haydn, she was thrilled to discover she was the first person to check it out in sixty years! The discovery gave her interest in music of the Classical era a considerable boost. I never minded my children being busy while I read to them: listening to books is a predominantly left brain activity, so keeping the right brain occupied actually helps the child concentrate on what she is hearing. She might color, do a puzzle, or build quietly, my only rule being that the noise of her rummaging through the box of Lincoln Logs must not drown out my voice. If she preferred, she could simply daydream—there would be no comprehension test. Indeed, none was necessary: I found each morning that when I reviewed the previous day’s reading before embarking on the next chapter, the children were invariably the ones helping me recall the action, not vice versa.

At some point in their development, all the children—boys included—enjoyed embroidery. I picked up Christmas ornament kits for next to nothing in July, and by late November we had several gems to add to the tree. Knitting too was highly popular. In liking to knit, Evan takes after the English grandfather he never knew, who used to relax by knitting fantastically intricate baby clothes whenever a close friend of the family gave birth. We probably looked like a scene from Little House on the Prairie, knitting and stitching while Mother read, but those were some of our happiest homeschooling times—and although Robin didn’t play the violin like Pa, at least he wasn’t moved to substitute the bagpipes.

I wondered if my tolerance for extraneous activity was hampering the children’s concentration. Seeing Lorna intent on her jigsaw puzzle, seemingly oblivious to the world around her, I asked her if she was able to follow the story. She looked up, surprise written all over her face. “Well of course,” she replied. “Why wouldn’t I?” To her, it was incomprehensible that the puzzle might be considered a distraction.

As the children grew older, their listening activities included tracing maps of the countries we were reading about, as well as coloring photocopied pages from historically appropriate Dover and Bellerophon coloring books. Tracing maps was the mainstay of their training in geography, apart from the hours spent at the kitchen table admiring the world map.

Over the years, we made salt-and-flour maps of the US, Israel, and Egypt, and once we fashioned the Far East out of mashed potato. I’m not particularly proud of this shortfall in geography education, but it worked for us, and the children’s knowledge of the countries of the world is better than many. At least they’ve never asked if you need a passport for New Mexico, or wondered if you can drive to Hawaii, as did one applicant for the position of receptionist in Robin’s office. And she was a college graduate!

To keep track of the books we read, I drew a rudimentary bookcase on a large piece of poster board, stuck it on the wall, and cut a generous supply of book spines of various heights and thicknesses from construction paper. Every time we finished a book, one of us wrote the title and author on a spine and stuck it on the bookcase. We all enjoyed looking over the books we had read—it gave us quite a sense of accomplishment.

Excerpted from Entropy Academy by Alison Bernhoft, full of easy and comforting homeschooling guidance and available here! Looking for more tips? See “Visual Materials,” “Science in the Kitchen,” and “Bath Time.” An excellent read-aloud option is Doniga Markegard’s young adult memoir Wolf Girl, which can be ordered here.

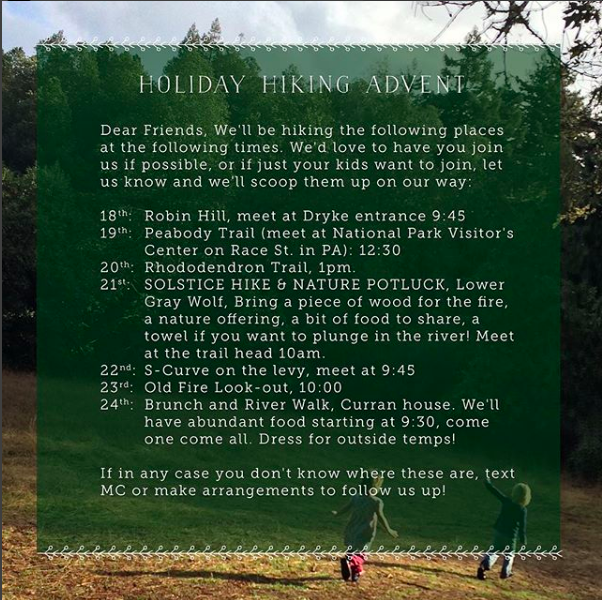

I usually choose one of three anchors for my walks. On some walks, I choose to attend to my breath, as I walk and become aware of certain thoughts, events, sensations, emotions or connections, I keep my awareness on my breath. This way I have a line connecting my attention to my breath and my whole experience organizes around it. A second anchor may be the ground. As I walk, I feel my contact with the ground—right, left, right, left—aware of the textures under my feet. A third anchor may be the colors around me—as my attention drifts I always come back to the colors and notice here is red, here is yellow. You can choose your own way to organize your walking meditations, and make this idea your own.

I usually choose one of three anchors for my walks. On some walks, I choose to attend to my breath, as I walk and become aware of certain thoughts, events, sensations, emotions or connections, I keep my awareness on my breath. This way I have a line connecting my attention to my breath and my whole experience organizes around it. A second anchor may be the ground. As I walk, I feel my contact with the ground—right, left, right, left—aware of the textures under my feet. A third anchor may be the colors around me—as my attention drifts I always come back to the colors and notice here is red, here is yellow. You can choose your own way to organize your walking meditations, and make this idea your own.

As for me, I’m excited to apply some of these tips to my December, and I hope you are, too! In my family, we called January 6 Little Christmas, and there was always a special meal, and a small gift for everyone around the table. I loved the way it brought forward the warmth of the season into the new year. From everyone here at Propriometrics Press, may that warmth be your companion long after the last gift is unwrapped and the twinkle lights are packed away.

As for me, I’m excited to apply some of these tips to my December, and I hope you are, too! In my family, we called January 6 Little Christmas, and there was always a special meal, and a small gift for everyone around the table. I loved the way it brought forward the warmth of the season into the new year. From everyone here at Propriometrics Press, may that warmth be your companion long after the last gift is unwrapped and the twinkle lights are packed away.